Inside the movement that’s rewriting how we do science

With new labs, funding models, and institutions, metascience is reinventing the machinery of discovery.

This piece was originally published in Big Think’s special issue, The Engine of Progress. In it, I provide my take on the talks and discussions around the metascience track of the 2025 Progress Conference.

Science is being rebuilt from the ground up. Across new institutions, tools, and funding models, a new generation of scientists and builders is rethinking how scientific and technological progress happens.

At the front of that movement is metascience, the study and redesign of how science operates. In the roughly six years since Patrick Collison and Tyler Cowen kicked off the “Progress Studies” movement, the metascience community has been marching forward across all dimensions. By establishing bold new formats of scientific institutions such as the Arc and Astera institutes, developing ambitious funding models such as the U.K.’s Advanced Research and Invention Agency (ARIA), and supporting a new frontier of Focused Research Organizations (FROs) through Convergent Research, the metascience community is making its mark outside traditional university models of scientific research.

These initiatives signal that the metascience movement has reached a turning point. What began as a conversation about the stagnation of science has evolved into an ecosystem of builders experimenting with new ways to fund, conduct, and distribute science. The excitement at this year’s Progress Conference underscores our movement’s collective realization that progress not only depends on increasing understanding but also on implementing change in the machinery of discovery.

AI for science

Artificial intelligence (AI) for science was one of the defining themes at Progress Conference 2025. Everyone from OpenAI CEO Sam Altman to Michael Kratsios, director of the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy, spoke about leveraging AI infrastructure to advance science. As a life sciences researcher who has tried to integrate AI into my experimental workflows but still spends long hours at the bench, I often find these discussions either too abstract or detached from the manual bottlenecks and slow feedback loops of research, but the talks at this year’s conference felt refreshingly concrete.

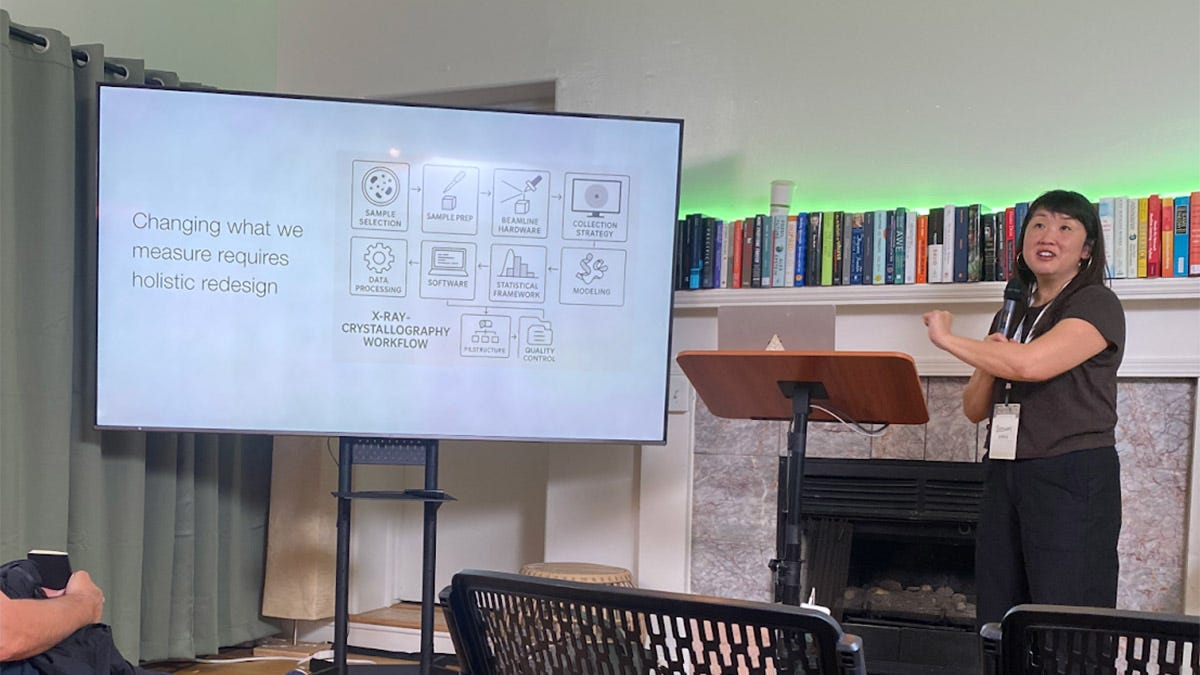

I was particularly struck by Seemay Chou’s presentation on re-engineering biological data generation for a world with AI agents. Chou, co-founder of Arcadia Science and the Astera Institute and board chair at The Navigation Fund, argued that as machines become active participants in research, science itself must be redesigned around AI agents as the primary operator. To make AI systems genuinely productive, she said, we need radically open, high-quality datasets that capture the full complexity of nature rather than curated subsets optimized for publication.

To put this vision into practice, Chou’s team is building what it calls the Protein Data Bank 2.0. The original Protein Data Bank has served as the central repository for three-dimensional protein structures for more than 50 years. Now numbering over 200,000 entries, it has been fundamental to breakthroughs like AlphaFold. Over 80% of the Protein Data Bank’s structures were determined using X-ray crystallography, and during the interpretation of X-ray diffraction data, much of the so-called “background” diffraction, which appears as fuzzy, low-intensity scattering that reflects alternative protein conformations or dynamic motion, is typically discarded, even though it contains rich structural information. Chou’s team, spanning Astera and several academic collaborators, is re-engineering this pipeline to retain and reinterpret that lost information.

The technical details matter less than the philosophy behind them: deliberately questioning decades-old conventions that simplified complex biological data for ease of human understanding. With AI as a research partner, we don’t need to strip away that complexity anymore. The messiness of biological data, all the signals buried in noise, may be exactly what provides context and helps machines uncover deeper structure. When I listen to Chou’s vision, I don’t just see it as modernizing crystallography; I see it as reimagining how humans and machines will work together to make sense of nature.

I also see this as a broader shift in the culture of science. In academia, experiments are typically designed to produce a cohesive story for publication, which often results in incomplete datasets or the absence of essential metadata needed for reproducibility. Throwing AI at those fragmented datasets is unlikely to yield insights; it will simply amplify the gaps. By treating the dataset — and not the paper — as the scientific output, Chou’s group is rebuilding the incentive structure from the ground up.

Their collaboration has taken a radical step by foregoing journal publications. Instead, all labs involved have agreed to release open datasets, lab notebooks, and even Slack transcripts as living records of discovery. The aim is to make the work so useful that it spreads by adoption, not citation. It’s a bold experiment in both infrastructure and culture, one that could redefine how research is done in the age of intelligent machines. There are, of course, many efforts to integrate AI into the analysis stage of science, but I’ve seen far fewer instances where the machine is treated as a true partner.

New research organizations

If Chou’s work represents a bottom-up reimagining of how scientific data is generated for the intelligence age, Anastasia Gamick’s vision takes a top-down view of how entire research systems must evolve to support it.

As the co-founder of Convergent Research, Gamick has spent the past four years designing and launching Focused Research Organizations (FROs), which are time-bound, startup-style nonprofits that fill the institutional gaps left between academia, industry, and government. She argues that progress stalls not because we run out of ideas, but because we run out of tools, such as shared datasets, instruments, and platforms that make new fields possible. By “pre-standardizing” the way research is organized, we have inadvertently optimized for individual breakthroughs instead of building the trunks of the technological tree that sustain all future branches.

FROs target the kinds of projects unlikely to receive traditional funding — the medium-scale, coordinated ones that are too engineering-heavy for academia, too pre-competitive for venture capital, too modular for mega-projects, and too focused for ARPA agencies. One example is E11 Bio, a neuroscience-focused organization building a brain connectomics pipeline using molecular, optical, and computational techniques that crush costs and enable brain-wide scaling. A project like this would struggle to find a home in academia, where grants typically support small, hypothesis-driven studies rather than multiyear engineering efforts to build core technologies. By investing in infrastructure, E11 Bio aims to make brain mapping orders of magnitude cheaper and faster, laying the foundation to address unanswered questions: how brain circuits are organized across the mammalian brain and how structure gives rise to function across the whole brain.

The early lesson I take away here is that, by systematically laying out the “trunks” and “branches” of the technological and scientific tree, we can uncover more FRO-shaped opportunities than expected, with lots of low-hanging limbs. I think the key is that FROs don’t replace the existing research ecosystem — they augment it.

I’m curious to see how the growth of these trunks plays out in the intelligence age. At least for now, true embodied intelligence, like the kind that can manipulate pipettes or align optics, is likely to emerge more slowly than cloud-based intelligence. Our ability to use AI agents for hypothesis generation, experimental design, and data interpretation will occur before robots take over the physical lab bench. That makes the human task clearer: to build the instruments, datasets, and collaborative platforms that these disembodied intelligences will need to operate effectively. In that sense, the FROs of today may be laying the groundwork for environments where both humans and machines can make discoveries.

Most of the new research models emerging from the progress community lean toward engineering-heavy capability building. That makes sense to me — AI will only unlock real discovery once the underlying tools, datasets, and platforms exist. But I also find that much of the conversation right now is concentrated on that side of the spectrum. Less attention is being paid to the exploratory, curiosity-driven work that has historically produced many of science’s paradigm-shifting breakthroughs.

We can’t do everything at once. It’s probably wise to start by building the right tools, and this new wave of alternative research structures is still in its early days. Still, I often wonder whether in our focus on infrastructure and capability, we risk overlooking the kind of open-ended inquiry that drives the biggest leaps.

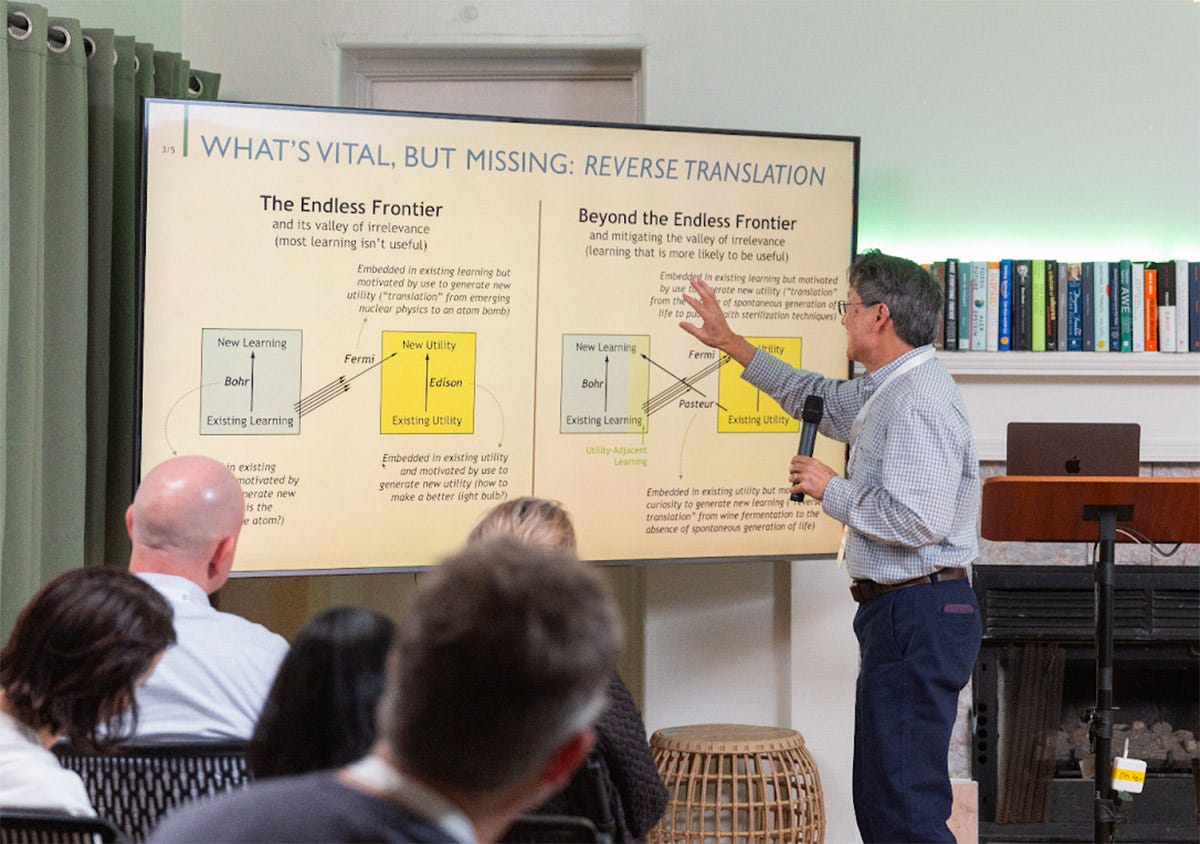

Jeffrey Tsao, a senior scientist at Sandia National Labs, offered one way to address this gap.

We often think of progress as a one-way street: scientists uncover new knowledge, which engineers then turn into tools and products. Tsao’s core claim is that the reverse path, where we use existing technologies and real-world systems as sites of discovery, can be just as powerful. By studying how technologies actually work in practice, we can uncover new scientific principles and generate knowledge that immediately connects back to use. He notes that this dynamic once thrived in the great corporate research labs of the 20th century, such as Bell Labs, Xerox PARC, and GE Research. Scientists at these firms investigated fundamental questions that emerged from the technologies they were building. When those labs disappeared, we lost not only the discoveries and innovations but also a unique model of how science and engineering can drive each other in a continuous loop.

Tsao’s vision resonated deeply with me. As a biomedical engineer, I’ve always been drawn to the intersection of technology and discovery, the place where a new instrument can make an old question answerable or unlock a whole suite of new questions. The most meaningful work, to me, is not building tools for their own sake but developing technologies that enable specific, previously unreachable insights about how life works. Progress isn’t just about identifying where science has stalled but about designing the institutions and mechanisms that help it move again.

Alternate funding models

Building new research organizations is only half the challenge. The other half is designing the incentive systems that allow them to thrive. Even the most visionary scientists can stall if trapped in rigid funding cycles or narrow review panels, and across the progress movement, a growing number of builders are asking: What if we redesigned the structure of funding itself?

One answer comes from Ilan Gur, the founding CEO of the Advanced Research and Invention Agency (ARIA), an R&D funding agency that has secured £1 billion from the U.K. government to engineer progress by rethinking how research is funded, not just done.

For Gur, progress is not an abstract concept but a systems-engineering problem. The challenge is not a shortage of ideas, scientists, or money; it’s that our massive, bureaucratic funding ecosystem scatters these resources too thinly to create the catalytic conditions where innovations happen. ARIA’s answer is to compress that reaction. Program directors are empowered to define bold “opportunity spaces” and then recruit top talent across disciplines and institutions to pursue them with flexible, milestone-driven grants. Gur’s formula is deceptively simple: align people, environment, and resources, and “magic happens.”

From my own experience, I’ve come to believe Gur’s equation captures something fundamental. People, environment, and resources are not interchangeable ingredients but sequential catalysts. You can have money and infrastructure, but without the right people, the system stays inert. The wrong environment can smother the creativity of brilliant people. Only when all three align does progress really ignite. I’ve seen how this sequence holds true. When the right minds are brought together and given the freedom to explore — the “free play of free intellects,” as Vannevar Bush once called it — resources become accelerants. Gur’s philosophy formalizes that intuition into institutional design. Instead of forcing people to fit pre-set programs, ARIA builds environments around them.

Tom Kalil, CEO of Renaissance Philanthropy, is also rethinking funding and incentives. He advocates shifting from “push” grants to “pull” mechanisms, which are like funding models that pay for outcomes rather than intentions, much like NASA’s partnerships with SpaceX or Operation Warp Speed. Caleb Watney, cofounder of the Institute for Progress, proposed X-Labs: large-scale, flexible grants to independent research organizations designed to explore bold, interdisciplinary questions that universities and startups can’t. Both approaches share a conviction that funding should act less like paperwork and more like propulsion by rewarding results, scaling what works, and giving science the institutional freedom to experiment with itself.

Ultimately, I find that what’s missing from today’s research funding ecosystem is not just more money, but incentives that encourage healthy competition between funders. Research funding in the U.S. remains remarkably one-dimensional. Most public science is funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and, to a lesser extent, the National Science Foundation (NSF), agencies that overwhelmingly fund small, principal investigator-led grants designed for an earlier era of individual inquiry. This structure rewards safety over exploration and leaves little room for institutional or methodological experimentation. Unlike in venture capital, where investors compete to identify and back the most promising, high-risk ideas, science funders face no comparable pressure to seek out unconventional bets or refine their own models.

The result is a stagnant funding ecosystem that selects for conformity rather than creativity. A truly dynamic research economy would mirror the process of evolution: many funding mechanisms, each taking different approaches, competing for the best ideas and talent. If we can build that kind of diversity in our funding landscape, with real competition and variation, we might restore the adaptive spirit that science depends on.

Looking ahead

One question that still feels unresolved to me is how we can best judge and support curiosity-driven research in a world that’s moving away from traditional academic structures like journals. Efforts to reform science have generally focused on building tools, platforms, and datasets, which are projects with clear deliverables that can be measured and funded in short cycles. But curiosity-driven research doesn’t fit neatly into that framework. For all their flaws, journal publications have at least provided a mechanism to evaluate and reward the early stages of long-arc inquiry.

Pull mechanisms like those proposed by Tom Kalil work well when success can be defined up front. But for exploratory work, where the outcomes are unknown by definition, that model might not be ideal. Michael Nielsen, a research fellow at the Astera Institute, and Kanjun Qiu, cofounder and CEO of AI startup Imbue, have proposed a “Century Grant Program” as a thought experiment — it would fund research for a hundred years through an endowment model. It’s a beautiful idea, but who, exactly, would be willing to take that bet, and on whom?

As we experiment with new funding structures and build the next generation of research institutions, this is the next challenge we need to face: How do we create the patience, trust, and evaluative frameworks needed to sustain slow, curiosity-driven science in a culture that prizes speed and measurable outputs? How will we recognize progress when it unfolds over decades and might only become visible long after its creators have moved on?

I left the conference feeling optimistic. The metascience movement is no longer just diagnosing the problems of modern research; it is building a new era of discovery. From AI-enabled data generation to FROs to new funding architectures, the community is learning by doing. If the past few years have shown anything, it’s that when the right people are given the freedom to build, entirely new possibilities for science — and for human progress — can begin to emerge.