Can We Engineer Creativity?

Or, the Boyden Paradox

One of the most creative scientists I know today is Ed Boyden. In 2005, while at Stanford, he and Karl Deisseroth developed a method to manipulate neurons with light called optogenetics. By using light-sensitive molecules from pond algae and inserting them into the brain cells of rats, they created a kind of remote control for the brain, where they could turn on or off specific neurons just by shining light on them. Using light, instead of traditional electrical stimulation, was a creative insight.

Optogenetics transformed circuit neuroscience. It enabled researchers to probe specific brain networks, such as those involved in memory, addiction, or Parkinson’s, and provide causal mechanistic explanations about their function. While optogenetics is far from being ubiquitous in the clinic (one does not simply genetically modify humans), it has a lot of potential. A 2021 paper showed the use of optogenetics to partially restore vision in a blind patient.

It’s rare enough for a scientist to transform their field once, but Boyden did it again ten years later. This time, instead of pond algae, he used baby diapers to develop a method called expansion microscopy. Typically, when scientists have tried to see small structures within biological cells, they have developed new imaging tools with higher magnification capabilities. Boyden was the first to flip the equation and ask: can we make the object itself bigger instead of making the microscope better? Inspired by the remarkable absorbing and swelling properties of a baby diaper, his lab developed a method to enlarge the brain. This method is now being used to map every neuron connection across the mouse brain.

Boyden has a method, which he calls Tiling Tree, to search the idea space for all possible ways to solve a given problem. This tool for thought enables him to think outside the box and search for ideas that might otherwise be missed. The tiling tree method contributed to the creation of both optogenetics and expansion microscopy.

If you have a system to generate creative solutions, is that still considered creative?

The creativity literature might say no, that creative ideas cannot be generated by systematic analysis. Papers on creativity suggest that the creative process cannot be algorithmic but rather relies on heuristics. This kind of creativity has of course played a role in many of the major scientific discoveries and innovations. Famously, Archimedes stepping into a bath and noticing the water level rise led to his eureka moment about buoyancy and displacement. Kary Mullis has said that the core idea for the Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) came to him while driving.

But intuitively, to me, both optogenetics and expansion microscopy are creative scientific innovations borne out of systematic analysis. This is what I’m calling the Boyden paradox. Is Ed Boyden creative or uncreative? And why does that even matter?

To answer whether Boyden is creative or not, we first need to define what creativity actually means. If we can understand what makes ideas truly creative, we might be able to generate more of them. We might even be able to engineer creativity and therefore discovery itself.

Defining creativity

I’ve been reading some literature on creativity, specifically the work of Dean Simonton, professor emeritus in the Department of Psychology at UC Davis. Simonton is known for his research on genius, creativity, and the factors that contribute to eminence across domains of science and art.

Simonton proposes that creativity requires three factors: originality, utility, and surprise. An idea is creative when we maximize all three. Critically, each factor is necessary but not sufficient, meaning that you need all three together.

Let’s define what each of these terms mean:

Originality: Simonton defines originality in terms of the idea’s initial probability (p). How likely was the individual to think of this idea when first encountering the problem? Original ideas have a low initial probability, meaning it’s unlikely that this particular person would come up with this idea when they first start thinking about the problem. On the other hand, unoriginal ideas have a high initial probability, meaning they’re among the first ideas that come to mind.

Since p (a probability) ranges from 0 to 1 (where 1 is highly probable and 0 is highly improbable), originality is defined as the inverse: originality = 1 - p. A routine idea with p = 1 gives originality = 0, while a low-probability idea with p approaching 0 gives originality approaching 1.

Utility: The idea’s final utility (u) indicates its usefulness, effectiveness, or value once the creator considers the solution finalized. Utility is a continuous variable between 0 and 1. While some problems have binary outcomes (u = 1 if it works, u = 0 if it doesn’t), many ideas have partial utility, where u falls somewhere in between when the solution works, but not perfectly.

Surprise: Surprise is defined in terms of the creator’s prior knowledge (v) about the idea’s utility (not the idea itself). At the moment of conception, does the creator know if it will work? Prior knowledge, v, is also between 0 and 1. If v = 1, the creator already knows the utility in advance; if v = 0, the creator is in the dark about the idea’s future utility.

Surprise is the inverse: surprise = 1 - v. When v is low, you learn something new by trying the idea, regardless of whether it succeeds (high utility) or fails (low utility). Surprise adds the dimension of time. It’s the change in knowledge through the creative process. This change in understanding from unexpected outcomes is what Simonton calls surprise or serendipity.

But why these three factors? Where do they come from?

When we call something creative, we usually point to work that stands out as something different from what came before. That’s originality. But difference alone isn’t enough. We also expect creative work to accomplish something, to solve a problem or produce value. That’s utility. There’s also a sense that the creator didn’t just mechanically apply known techniques. There’s an element of discovery, of the creator learning something through the process. The outcome wasn’t obvious or guaranteed beforehand. That’s surprise.

These three factors emerge from how we use the word “creative.” We don’t call routine work creative, even when it’s useful. We don’t call random novelty creative if it serves no purpose. And we usually don’t call the straightforward application of expertise creative, even when it produces excellent results. Creativity seems to require all three: trying something unusual that works in ways that weren’t fully predictable.

Regardless of whether you agree that these three factors exactly describe creativity, let’s assume it does and continue with Simonton.

Simonton formalizes his concept of creativity through the following equation:

Creativity = originality · utility · surprise, or

C = (1-p) · u · (1-v)

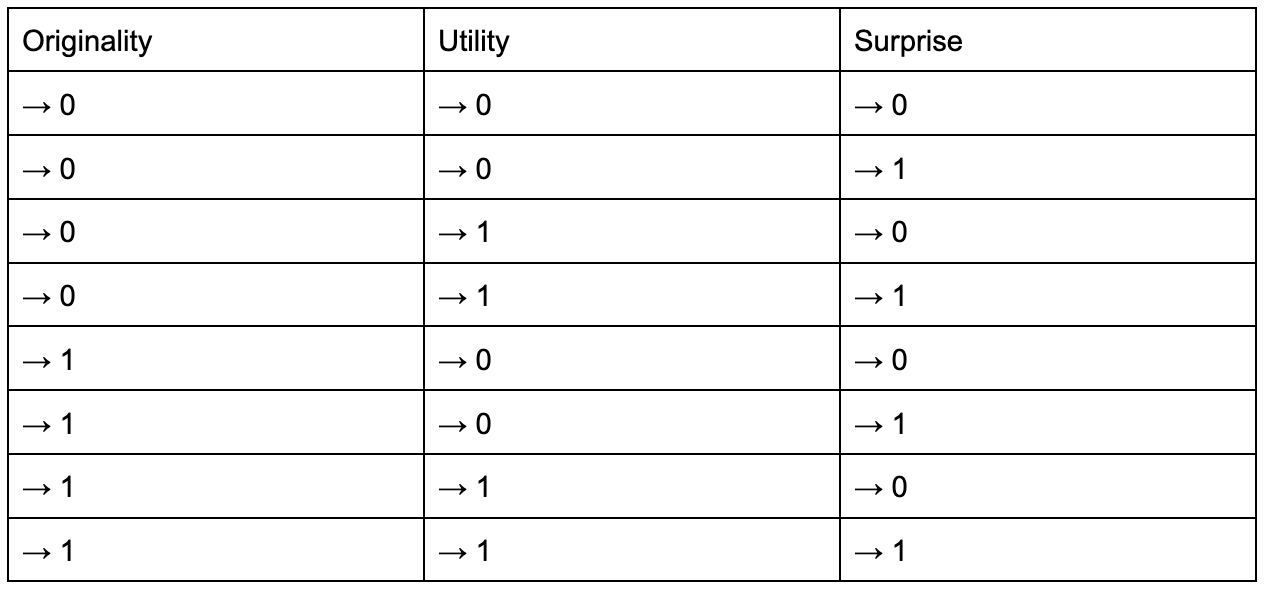

To make this concrete, Simonton identifies 8 possible combinations when p, u, and v approach either 0 or 1. I found this exercise helpful for comparing different types of ideas:

There are seven ways to be uncreative:

Case 1: Originality = 0, utility = 0, surprise = 0 (irrational repetition)

No originality, no utility, no surprise. This is doing something habitual that you know doesn’t work, like checking your jacket pocket for car keys for the tenth time when you know they’re not there. “The definition of insanity is doing the same thing over and over and expecting different results.”

Case 2: Originality = 0, utility = 0, surprise = 1 (problem finding)

The idea is routine but you’re surprised it has no utility. A home example: you make sourdough with your usual starter, but this time the bread doesn’t rise. Nothing novel about your process, but you expected it to work. This surprise reveals hidden problems – maybe the starter went bad, or the temperature was off. A lab example: a routine calibration failing can reveal instrument problems. Problem finding isn’t creative itself, but it can lead to creative solutions.

Case 3: Originality = 0, utility = 1, surprise = 0 (routine, habitual ideas)

This describes most of our day-to-day thinking. Ideas we’re likely to generate that we know have high utility: your usual route to work, routine cell media exchanges, your toddler’s bedtime routine. Habits that let us navigate everyday life. Nothing extraordinary.

Case 4: Originality = 0, utility = 1, surprise = 1 (lucky guess)

Nothing original, but you’re surprised by the positive outcome. An action that usually has no utility ends up having unexpected value. You buy lottery tickets every week with no wins. One day you win big. Buying ticket number 100 wasn’t creative, your expectation of payout was low, but you’re surprised when it pays off.

Case 5: Originality = 1, utility = 0, surprise = 0 (rational suppression)

High originality but low utility, and you knew ahead of time it wouldn’t work. Like trying to expand the brain by stretching it with your hands. It would be an unusual idea, but you’re confident it won’t work. You use expertise to rule this out, consciously or unconsciously.

Case 6: Originality = 1, utility = 0, surprise = 1 (blissful ignorance)

This one confused me. It suggests an original idea where you were surprised it didn’t work. Meaning you thought it would succeed but it failed. Overconfidence from expertise, perhaps. But Simonton calls this “blissful ignorance” where an idea is never tried. This reveals how parameter values matter: are we setting them to exactly 0, or approaching 0? There’s some inconsistency in Simonton’s treatment.

Case 7: Originality = 1, utility = 1, surprise = 0 (irrational suppression)

An original idea with high utility that you know will work, yet you rarely do it (low initial probability). Deliberately not doing something you know is good for you: exercise, eating healthy. A science example might be sticking with traditional methods when better ones exist, like continuing to use outdated statistical methods, or avoiding better model organisms.

One way to be creative:

Case 8: Originality = 1, utility = 1, surprise = 1 (maximum creativity)

Finally, the creative case. After seven ways to be uncreative, it’s clear why we need to maximize all three factors. Low initial probability (originality) indicates that the idea isn’t obvious. High utility indicates that the idea needs to work. Low prior knowledge (surprise) indicates that you don’t know ahead of time it will work.

Expansion microscopy as an example

Let’s see how expansion microscopy satisfies all three criteria:

Originality: When everyone else was working on making microscopes better, Boyden thought to make the object itself bigger. This had low initial probability; It isn’t among the first ideas that come to mind when thinking about imaging small structures. Most microscopists would naturally think about improving lenses, detectors, or light sources, not inflating the sample. Originality ~1.

Utility: The technique works. Scientists are using expansion microscopy to map brain networks at single-cell resolution. Groups beyond Boyden’s lab have adopted it. For instance, E11 Bio is using it to map every neuron connection in the mouse brain. The method has also proven useful across many applications. Utility ~1.

Surprise: Boyden didn’t know ahead of time whether swelling brains would work. There was a significant chance the effort failed – the brain could have torn apart or the cellular structure could have distorted. There was genuine uncertainty about whether this approach would preserve the precise spatial relationships scientists needed to see. Only by trying it did they learn it worked. Surprise ~1.

With all three factors maximized, expansion microscopy scores high on creativity: C = (1-p) · u · (1-v) → 1.

Resolving the paradox

A key component in the creativity field (yes, there is a creativity field) is that problem solving must be heuristic rather than algorithmic for ideas to be creative. Once you have a procedure to generate solutions, it ceases to be creative.

But this is exactly what Boyden has done. He believes that “creativity, and problem solving, like any other skill, can be learned and taught.” In his tiling tree method, you start with a problem and systematically map out all possible solutions. He claims this forces you to consider solutions you would normally not think of.

Boyden’s group uses this method regularly. It played a role in both optogenetics and expansion microscopy. And he’s not alone. Fritz Zwicky, a Swiss astronomer, developed his own systematic method for investigating complex problems. Using this approach, he coined the term “supernova,” described neutron star formation, and was the first to propose dark matter.

To me, this is engineering at its best. Taking the process of discovery and reverse-engineering it to become reproducible. Meta-creative, if you will: becoming creative about your own creative process.

This seems to directly contradict the creativity literature, which excludes systematic ideation as creative. But maybe Simonton and Boyden aren’t actually in conflict. Maybe they’re describing different aspects of the same process.

Boyden’s Tiling Tree Method doesn’t eliminate the need for uncertainty or a flash of insight. Instead, it’s a systematic way to find the uncertain ideas worth pursuing. The tree maps the solution space comprehensively, forcing you to consider branches that seem unlikely or unreasonable. But you still have to choose which branch to climb without knowing if it will bear fruit.

The method lowers p (makes you think of unusual ideas) without raising v (you still don’t know which will work). This preservation of uncertainty is crucial. As Michael Nielsen has argued, scientific breakthroughs often require a willingness to pursue ideas that don’t yet make rational sense. A perfectly rational actor would only pursue ideas with high known utility. But those are precisely the uncreative ideas in Simonton’s framework. Creative breakthroughs require taking bets on low-v ideas.

In this sense, Boyden isn’t necessarily engineering creativity itself. He’s engineering the conditions that make creative insights more likely. He has even talked about this process as engineering serendipity. He’s systematizing the search process while preserving the essential uncertainty that Simonton argues is necessary for creativity.

Some unresolved thoughts on Simonton’s framework for creativity

I find the qualitative concepts of originality, utility, and surprise useful for discussing creativity, but I’m unsure about the quantitative aspects. Simonton offers an equation, but provides no method for assigning numbers. How original is expansion microscopy? We know it has high originality, but is that 0.8 or 0.99? What would the difference between those numbers even mean?

Similarly, we know expansion microscopy has utility, but it also has limitations like uneven expansion in certain tissue types, for instance. Does that make u = 0.95 instead of 1.0? How much does each limitation reduce the utility score?

More fundamentally, how would one actually apply this equation? Consider a thought experiment: two people in different rooms independently solve the same problem. One describes the solution in two pages of detailed prose; the other gives a succinct one-paragraph explanation of the same solution. The longer description has lower probability of occurring than the shorter one (fewer people would spontaneously write exactly those two pages). Does that make the verbose solution more creative, even though both produce the same result?

Another aspect is expertise. Let’s take another situation with two people in different rooms solving the same problem, this time let’s assume they each come up with a similar one-paragraph description, except now one individual is a domain expert while the other is not. Given that the domain expert probably has a higher likelihood of coming with that solution, does that naturally always make a novice more creative?

Finally, how does creativity in the arts fare with this equation? How do I quantify the initial probability or surprise at the utility of Picasso’s work? Does this framework suggest Picasso was creative, and was he more or less creative than Matisse? There’s a line in the movie Midnight in Paris where a character in the 1920s claims, “Matisse is the greater painter, but Picasso is the greater artist.” While completely fictional, the distinction is telling: “artist” implies creativity, while “painter” suggests skill or technical mastery. Can Simonton’s equation capture this difference?

Can we engineer creativity?

Maybe you can’t engineer the creative idea itself since that would raise v and kill the surprise. But perhaps you can engineer the process that generates creative ideas. You can create systems for exploring the improbable. You can develop algorithms for finding heuristic problems. Boyden’s Tiling Tree doesn’t guarantee which branch will succeed (keeping v low), but it systematically forces exploration of low-probability solutions (lowering p for unusual ideas).

Why does any of this matter?

First, I’m interested in understanding how scientific discoveries happen. Creativity plays a crucial role in major breakthroughs, from penicillin to CRISPR to optogenetics. If we can develop a robust theory of the creative process, we can build environments that enable creative outputs.

Second, generative AI presents an interesting test case. We often ask whether ChatGPT is creative. Can we apply Simonton’s equation to formally evaluate it? Based on the complications we’ve explored, any straightforward application seems problematic: a more verbose model that adds filler text would rank higher in originality simply because longer outputs have lower initial probability.

If we can develop a robust, quantitative theory of creativity, analogous to what Shannon did for information theory, that could transform how we build AI systems. What would an LLM or image model be capable of if we could optimize with a rigorous measure of creativity?

I don’t have the answers to all these questions, and I’ve only scratched the surface of Simonton’s work, let alone all the other literature and commentary on creativity. I find Simonton’s framework useful for thinking about it, even if I have questions about the applicability of the math.

I’m very much thinking out loud in this essay. If you made it this far, and are interested in discussing any of these ideas, please DM me or drop a comment!

My interest in exploring Simonton’s research comes from some very interesting conversations with Jeff Tsao. Thanks to Gavin Brown for all the discussions and feedback on the drafts of this essay.

Cover Photo: Photo of Picasso working on Guernica. Source.